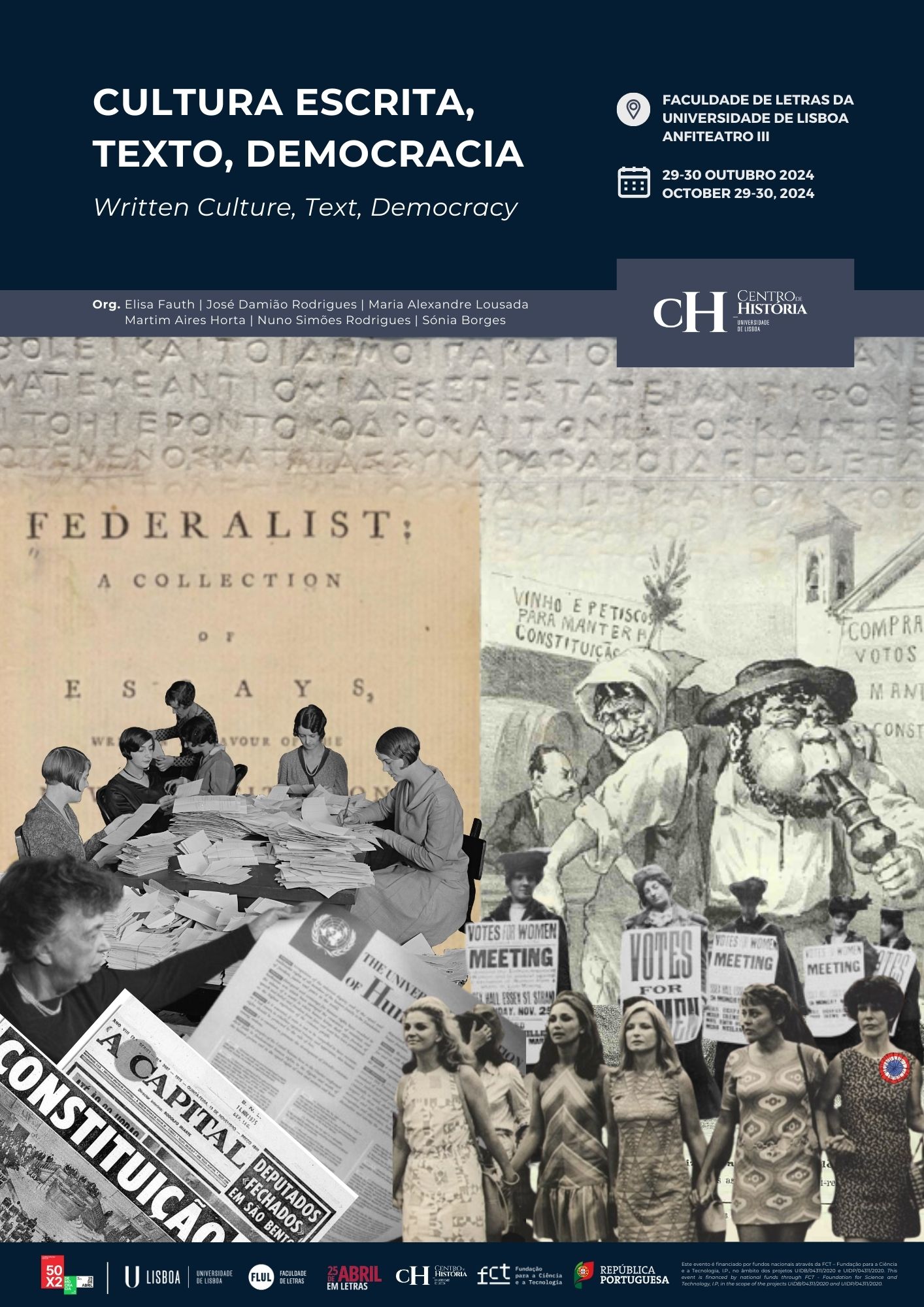

Colloquium

Written Culture, Text, Democracy

[Portuguese version]

School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon (Auditorium III)

October 29-30, 2024

Organising Committee | Elisa Fauth, José Damião Rodrigues, Maria Alexandre Lousada, Martim Aires Horta, Nuno Simões Rodrigues e Sónia Borges

Organisation | Centre for History of the University of Lisbon

Support | Comissão Comemorativa 50 Anos 25 de Abril

Download poster | Programme | ZOOM LINK

To celebrate the 50 years of the Portuguese Democracy, the Centre for History of the University of Lisbon is organising a colloquium on the texts and the written culture in the History of Democracy. It intends to explore the relationship between writing and democracies through two main approaches: that of the theory in the texts that comprise the traditions, debates, and perspectives on Democracy; and that of the practice of texts and writing in democracy, its materiality and support. Bibliophile and bibliophage, Democracy depends on texts, on writing and reading.

Presentation

Democracy is prone to profusely produce and make use of paperwork, and democratic culture is one of reading and writing. For long periods of time in History, democracies seemed to exist only on paper, one that preserved the memory of Antiquity’s emblematic experiments, but also kept envisioning new proposals, some more utopic, others striving for a degree of realism. Modern democratic systems are beneficiaries of these past experiments, traditions, theories, schools of thought, and worldviews. And for many of those living in democracies, Democracy seems ever out of reach, brilliant on paper, but lacking in practice. Lofty promises and expectations often fall short in its historical realisations, enfranchisement and emancipation is often limited, sometimes by design, and the democratic system is itself marked by the incomplete nature of its accomplishments, as criticism, renewal and revision are integral to its functioning and development, without establishing a finished stage for society nor an end of History.

As a system that institutionalises and depends on methods of permanent deliberation and adjustment of its legal framework, Democracy multiplies the use of paper as a medium to think, convey information, organise, and bring about change. What might start in petitions and pamphlets is then published in studies and reports, might move public opinion in newspapers and be debated in legislatures, with its discussions being transcribed in minutes and proceedings, to agree on a version of a text to be granted the force of law. Meanwhile, democracies need experts to write and interpret their documents, written according to traditions in style and schools of thought that establish their symbols and semantics. Elsewhere, leaflets, posters, periodicals, and books proliferate on any subject of the day. Democracies establish libraries and maintain archives, but they also have their restricted texts, forbidden books, noncanonical literature, and marginal authors, as even their critics have a place. Written culture in democracy is inseparable from freedom of speech, from the polyphony of voices and the plurality of opinions.

It is a persistent truism to state that democracies need an informed citizenry, but they likewise require readers and writers. Growth in alphabetisation and literacy rates often accompany democratization processes, as well as periods of particular and intense written production, both literary and political: the efflorescence that follows the full use of creative freedoms in open societies. Reading and writing is necessary for democrats and their system. While democracy is an ideal that establishes institutions dependent on the free and individual decisions of its citizens, its practice materializes texts that support the methods and art of governing, as well as the means for the members of society to deliberate and participate. Take the metonymic ballot paper, for example, in many ways the quintessential symbol of modern democratic elections. It is a piece of paper where one reads and writes. It lists a group of names that were previously validated by specialized institutions, after groups of citizens have filled the required paperwork and provided dossiers with lists of signatures of support. Those institutions had to check those documents against other dossiers and databases to establish if each candidate meets the criteria to be eligible. To exercise our voting rights, we present another piece of paper, a card that proves we are who we say we are, and give it to a poll worker, often a stranger to us, in whom we trust to independently verify who we are in voter rolls and call our name out loud.

Despite the progressive immateriality of documentary production and consumption related to the working of modern democracies, of which expansive bureaucracies have followed their historical development, paper persists as essential. It operates as proof of validation and accuracy of information, sometimes above the testimony of the citizens themselves, with strange ontological certainty: the affidavit, the certificate, the diploma, the bill, the duplicate, etc. Throughout their lives, citizens end up collecting a personal archive of documents that prove who they are and what they can do among their fellow citizens. In the aggregate and to a larger extent, democracy also collects and categorizes documentation, and access to it is seen as fundamental for transparency and democratic scrutiny. To control the access to the documents relevant to citizens grants some degree of power and leverage to those who wield it. To keep documents hidden from the public is a grave accusation, and to forbid its disclosure goes against what is expected of democracies.

To celebrate the 50 years of the Portuguese Democracy, the Centre for History of the University of Lisbon is organising a colloquium on the texts and the written culture in the History of Democracy. It intends to explore the relationship between writing and democracies through two main approaches: that of the theory in the texts that comprise the traditions, debates, and perspectives on Democracy; and that of the practice of texts and writing in democracy, its materiality and support. Bibliophile and bibliophage, Democracy depends on texts, on writing and reading.

Programme

TBA

Programa

(October 29th)

9.15 a.m | Opening Session

Maria Alexandre Lousada, José da Silva Horta (University of Lisbon)

Hermenegildo Fernandes (University of Lisbon) | O paradoxo do goliardo. Cultura escrita, mobilidade social e democracia. Uma visão do interior da Universidade.

10 a.m | Session I | Democracy and Written Culture in Ancient Greece

Moderator: Nuno Simões Rodrigues

Paul Cartledge (University of Cambridge) | Assassination, Elections, and Democracy - ancient Athenian-style.

Irene Polinskaya (King's College London) | Wind and Fog in the Hall of Mirrors: Writing Culture in the Athenian Democracy.

Delfim Leão (University of Coimbra) | The Seven Wise Men and their Letters in Defence of Law and Democracy: a Literary Forgery Rooted in Biographical and Historical Tradition.

12 a.m | Session II | Horizons and Pre-Democratic Experiences

Moderator: José Damião Rodrigues

Marco Alexandre Ribeiro (University of Lisbon) | Experiências democráticas na Idade Média: reflexões em torno da participação política popular a partir da "contra-hegemonia" de Gramsci.

Diogo Pires Aurélio (University of Porto) | A crítica das Escrituras na génese da democracia moderna.

Nuno Gonçalo Monteiro (University of Lisbon) | Petições, requerimentos e representação política no Antigo Regime.

3 p.m | Session III | Text, Democratisation, Decolonisation

Moderator: Carlos Almeida

Paula Morão (University of Lisbon) | José Gomes Ferreira, testemunha de revoluções - 1910 e 1974

Maria do Rosário Pedreira (LeYa Group) | Ler. Saber. Dizer Não

Augusto Nascimento (University of Lisbon) | As contingentes palavras escritas e democracias em São Tomé e Príncipe.

Sarita Mota (Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon) | Escrita de direitos: do “papel passado” à inclusão social na democracia brasileira.

5.30 p.m | Closing Session I

Moderator: Maria Alexandre Lousada

Janaína Martins Cordeiro (Fluminense Federal University) | Mães do ano: participação feminina conservadora e ditadura no Brasil

(October 30th)

9.30 a.m | Session IV | Text, Theory and Practice

Moderator: Ricardo de Brito

Sérgio Campos de Matos (University of Lisbon) | História, nação e concepções de democracia no republicanismo português.

Ernesto Castro Leal (University of Lisbon) | Programas políticos republicanos e socialistas em Portugal: lugares de construção do discurso democrático (1891-1926).

António Pedro Barbas Homem (University of Lisbon) | Constituição e cultura constitucional.

11.30 a.m | Session V | Text, Democracy, Comunication

Miriam Halpern Pereira (Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon) | A palavra ao povo: os jornais O Procurador dos Povos e O Democrata (1838-1840).

João Esteves (Independent Researcher) | Do pensamento à ação, da palavra à mobilização: os textos "esquecidos" na complexa construção da cidadania feminina no dealbar do século XX.

José Neves (University of Lisbon) | Sobre a escrita sem autoria: comunismo e trabalho na democracia portuguesa.

2.30 p.m. | Session VI | Text, Christianity and Democracy

Moderator: Paulo Fontes

Rita Mendonça Leite (Portuguese Catholic University) | Os textos do cristianismo como fontes dinâmicas de diversificação e democratização: livro(s), escritura(s) e leitura(s).

Edgar Silva (Portuguese Catholic University) | Manifestações do catolicismo de vanguarda durante o Estado Novo.

José Augusto Ramos (University of Lisbon) | Traduzir a Bíblia em Horizonte de Democracia.

4.15 p.m | Session VII | Memory, Archives and Democracy

Comentator and Moderator: Pedro Estácio

António Araújo (Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation) | «O Mais Sacana Possível»: A revista Almanaque (1959-1961).

Irene Flunser Pimentel (NOVA University of Lisbon) | Arquivos e democracia: os arquivos da PIDE/DGS.

José Pacheco Pereira (Ephemera Archive) | Arquivos e Democracia.

6 p.m | Closing Session II

Moderator: António Pedro Barbas Homem

António Costa Pinto (University of Lisbon) | Pluralismo limitado e cultura escrita na transição democrática Portuguesa.